One statement most of us will have heard – or even mentioned ourself is: “If there’s no age statement on a bottle, it’s 3 years and a day old”. Because that’s the legal minimum a whisky has to mature in oak barrels to be called Scotch Whisky – regardless of it being a blend, blended malt or single malt. But is said statement true? How old is the majority of Scotch when it is bottled and how much is allowed to mature for double-digit years? How do production and sales numbers compare? Lucky for us the Scotch Whisky Association (SWA) publishes yearly reports with numbers to crunch and relate. The downside is, the publicly available detailed reports only range from 2009 till 2013, with the 2014 data expected in the fall of 2015. While not ideal it’s better than nothing and with lots of calculations and spreadsheet magic we’re able to condense the data into more digestible summaries.

Before we get into the details and analyses, a word of warning: The SWA report only contains data from their member companies (which represent roughly 95% of Scotland’s distilling capacity), and, in the case of the “CHANGES IN BULK STOCKS BY TYPE AND YEAR PRODUCED” report, all the stock maturing in warehouses owned by SWA members (which may contain whiskies/spirit from non-member companies). The SWA represents the vast majority of distilleries, so we don’t run into too much trouble, but when we’re comparing and combining the SWA figures with figures from HM Revenues & Customs when we get to the export volumes (which include all distilleries in the UK), we are introducing a margin of error. The SWA publishes the warehouse (bulk stock) inventory numbers based on calendar years. For the sake of compiling this report I am converting the calendar years to the respective age of the whiskies, which is technically not 100% correct, but the only way to make the numbers comparable even though this also introduces a certain margin of error as a barrel of whisky will progress from say 5 to 6-years old within the course of a calendar year (unless it’s distilled on the first of January…). Also note, this method also does not correspond 100% to whisky actually being bottled (not accounted for are for example unknown volumes of casks being transferred to/from non-SWA member warehouses or breakages/leakages) but in total absence of such figures (in relation to the age of the whisky) we have to play the hand we’re dealt. In the end the data derived from the “bulk stock” (warehouse inventory) tables (especially the “changes” column) lines up with the export values from HM revenues and customs, making me confident in the validity of the chosen approach. All data (including customs data) is sourced from the public SWA reports, all interpretations and views (as well as calculation errors, should I have made any, ahem) are my own. Should you notice any errors or have additional information – get in touch!

All figures are based on LPA (litres of pure alcohol).

All right, without further ado, let’s take a look at those stats and figures.

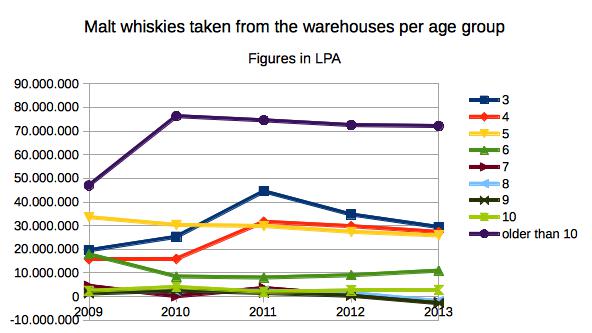

Whiskies extracted from the warehouses

First of all, let’s take a look at the volume of malt whisky at 3 years+ taken from (or added to, see about that later) the warehouses per year between 2009 and 2013:

This chart reveals several key points about how malt whisky is used in the industry:

– The age group of whiskies aged for longer than 10 years is the highest figure. However, it does represent a highly diverse group from 12-year-old mass-market standard expressions to the aged single cask market and old, luxury whiskies. This category is just about useless in its current form, if anything it only shows a current downwards trend and without previous data I cannot explain the rapid increase between 2008 and 2009.

– Three-, four- and five-year old whiskies are very close together, with about 30 million litres each in the year 2013. There is a distinct difference, however: While three- and four-year-old whiskies were on the rise between 2009 and 2011 (and have since gone down slightly – more about that later) the usage of five-year-old whiskies has steadily decreased in the same timeframe, indicating that the general mix of what goes into the bottle is getting younger. Keep in mind, we cannot differentiate between blended whisky, blended malt and single malt here, the data isn’t there! However, with the massive expansion of the no age statement category, mostly made up of very young whiskies, it wouldn’t surprise me at all if all types of Scotch were affected.

– Take a close look at the curve for six-year-old whisky: It’s gone down considerably, from nearly 18 million litres of pure alcohol in 2009 to 8.5 million litres in 2010 rising only slightly to just shy of 11 million litres in 2013, also indicating the continued use of younger malts.

– Seven-, eight-, and nine-year-old whiskies only played a very minor role with varying amounts between just 140.000 and 5.000.000 litres whereas 10-year-old whiskies, the core age for many single malts, remained more or less stable at roughly 2.5-3 million litres per year with a slight spike at 4 million litres in 2010.

– There were INcreases for whiskies distilled in 2004, 2005, 2006 in the 2013 report. No explanation is given. I can only speculate on the reason being stocks from non-SWA companies being transferred to SWA companies or their warehouses in 2013. (let me know if anybody should have or find more info about that…)

Let’s take a look at grain whisky next, the bulk of which goes into blends:

This chart looks familiar, but there are also several differences to the malt whisky chart:

– Three-year-old grain whiskies form the vast majority – used for standard, (mostly) cheap supermarket blends

– Four- and five- year old grain whiskies are trailing behind those only matured for the legal minimum, with an interesting, but unexplainable draw between the three- and four-year old whiskies in 2012 – a trend which was reversed again in 2013

– There’s a general downwards trend from 2011 on for nearly all but the three-year-old grain whiskies, especially visible in the 10+ category. A sign of drinkers of more premium blends changing to single malts? We’ll take another look at that later on.

– While the 10+ category made up the largest volume in the malt market it is of lesser importance in the grain whisky market, which is no wonder since grain whisky is first and foremost the base for the large volume of cheap(er) blended malt.

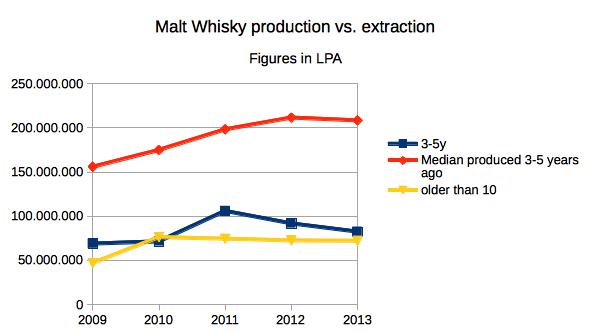

Malt whisky production vs. usage

This diagram needs some explaining: I have aggregated the data for all 3-5 year-old malts extracted from the warehouses per year, since these form the majority of whiskies used as we established earlier on. The red line represents a three-year median of new make production back when these three-to five year-old whiskies were made so we can compare how production and actual demand, when the whiskies have become “ready”, correlate. For comparative reasons I have also included the graph for the amount of 10+ aged whiskies taken from the warehouses at the same time.

This diagram needs some explaining: I have aggregated the data for all 3-5 year-old malts extracted from the warehouses per year, since these form the majority of whiskies used as we established earlier on. The red line represents a three-year median of new make production back when these three-to five year-old whiskies were made so we can compare how production and actual demand, when the whiskies have become “ready”, correlate. For comparative reasons I have also included the graph for the amount of 10+ aged whiskies taken from the warehouses at the same time.

– Production has increased on a steady level foreseeing rising demand before being throttled again in 2009 (209m LPA) and 2010 (191m LPA) – as can be seen in the 2013 chart where these production levels are taking effect in the median calculation. From 2011 onwards (not shown in the chart) there was a rapid increase in production again with a record year in 2013 of 274.784.185 litres of pure alcohol (malt only).

– For the first half of 2014, the SWA reported an 11% decline of all whisky exports (in value, not volume!), it will be very interesting to see whether this trend of increased production and falling sales will continue.

– From 2010 on, extraction of 10+ year-old malts has gone down slightly year after year – after a huge jump between 2009 and 2010. Once again, I have no access to detailed data prior to 2009 which would be very interesting as 2009 marked the start of the current worldwide economic crisis. The only data available is overall export volumes of whisky, which were down in 2008 (302m LPA), 2009 (304m LPA) and 2010 (297m LPA) compared to 2007 figures (318m LPA). These figures, however, include all types of whisky, so we can’t use them as comparison, only as an indication.

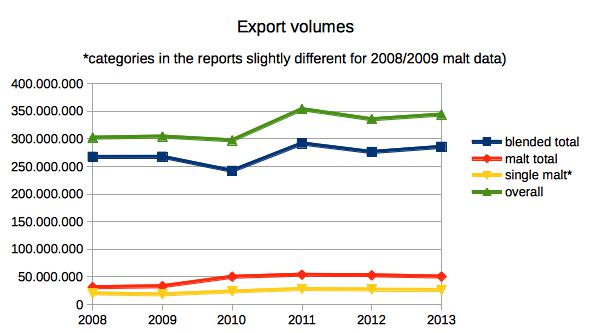

Export volume 2008-2013

Taking a quick look at the export volumes between 2008 and 2013 we can confirm what we’ve seen when we took a look at the warehouse extraction numbers: Until 2011 volumes were rising. They have since flatlined (down in 2012 and slightly up again 2013) for the overall and the blended whisky market and they have been slightly down in 2012 and 2013 for the overall malt and the single malt market respectively. Earlier on I asked the question whether blend drinkers tended to switch to single malts – the data doesn’t seem to support this, especially given the higher volume of the blended whisky market. Or maybe there’s a balance between those giving up on single malts due to steadily increasing prices and those switching from blends? Who knows – and I know I’m reaching here, there’s no valid data to support such thoughts…

Takeaway messages

– Yes, the majority of Scotch whisky (blends, blended malts and single malts altogether) is 3-5 years old, just as expected.

– The warehouse / bulk stock figures indicate increasingly younger whiskies being bottled

– Overall production is up, worldwide exports are flat with a slight downwards tendency (but still on a very high level compared to 10 years ago).

– Remember, all these stats and figures are valid only for the SWA-represented part of the industry as an entirety. Sadly no specialised data for sub-markets, like well-aged single malts, which we single malt enthusiasts are most interested in, is available.

– If the production and sales trends continue, more mature malts will be available in future years (older stock replenishment)

– Until then well-aged malts might just become scarcer and continue to get more expensive

– 2014 (and 2015) data will be very interesting to see where the direction is going and whether the trends outlined here continue, I’ll post an update when the reports are available.

Hi Klaus! Thanks for doing all this. I can never be bothered to comb through reports like these, and am very thankful that there are people like yourself willing to distill the info. Great service for the lazier ones like myself 🙂

One of your takeaway messages is that we’ll see (if trends continue) more mature malts in future years. Do you have any idea what time frame were talking about?

Thanks, Thijs, it isn’t the easiest of tasks sifting through the data, but in the end it’s worth it 🙂 I really don’t feel confident in predicting the break-even point from the top of my head, I’ll look into it in detail when I’m back home. Probably it’s in the range of 5-10 years for the 10-15yo drams, but that’s a very long time, a lot can happen and the data is only valid for the industry as a whole, not for individual companies/brands which makes it even more difficult …

Either way, patience is key 🙂 Not based on any facts, but I think it is fair to say that somewhere in the distant future (20, 25, maybe even 30 years away) there’ll be a new malt whisky lake, not unlike one that came about after the whisky depression of the eighties. History in the whisky industry has repeated itself over and over, why would this time be any different?

Who knows what will happen… Sales currently plateau at a very high level – a level which is unsustainable at the current rate in regards to older malts aged 10 years+ which is the true reason behind increasing numbers of young and NAS whiskies. Demand is slowing down, but we drank too much of the old stuff while demand was rising during the last decade, paired with lower levels of production back then. I can definitely see a part 2 to this article coming up, lots of questions left and quite a bit more data to sift through 🙂

Hi Klaus,

Very impressive report! Really cannot imagine how long it took you to do all this, but I’m glad you did. I think I’ll be referring to this quite often in the near future. Very helpful stuff! We can all be hopeful for the future of whisky, it seems, although we all have to be patient. In the mean time, let’s enjoy a nice dram every now and then, even if sometimes they are 3 to 5 years old…..:)

Thanks, Geert, I appreciate the feedback and am glad to read it’s helpful – that was certainly my intention! The future of whisky is decided right now, which is why I’m so eager to get my hands on current data. First indications show another decline in the market, yet production was at full steam in 2011-2013 (and I assume 2014 will have been no different), leading to a rising amount of unused stock which is left to mature longer than initially intended (with the bulk of whisky being used between 3-5 years of age). Interesting times! Something to ponder over a wee dram or two, be they young or old.

A lot of people argue about what the expiration of a good whisky should be after they are bottled at the manufacturing factory. I feel like its debatable and people should stop worrying so much.